What Is “Empathy?”

Most clinical and counseling psychologists have identified a core set of three distinct skills required in the truly empathic person:

- the ability to share experience,

- the cognitive ability to intuit, or mentalize (and perhaps understand) what another person is feeling, and

- a “socially beneficial” intention to respond compassionately to that person’s distress .

One thing humans are genetically predisposed to do, is identify patterns. It’s built into our DNA as a protection mechanism. Our life experience teaches us to identify what is helpful verses what is hurtful. Our brain sorts out these stimuli and decides how to categorize them: good, bad, fun, painful, tasty, arousing, disgusting, joyful, etc.

Our World Is Not “Black and White.”

Of course, one of the first realizations we come to is that the world is not binary (0s or 1s, either on/off or good/bad). In reality, things are much more complicated.

For example, we need water to survive, but we can also drown in water. Water is not inherently good or bad. It depends upon the context.

In other words, there is a continuum upon which water can represent any number of things: a cure for dehydration, a method of transportation, an impenetrable barrier, a tsunami that can destroy, or a rain storm that can nourish crops. When you learn to recognize the many manifestations of water in this continuum, you know how to best deal with it.

The same thing with temperature is represented on a continuum known as a “scale.” If the temperature is too low, it’s freezing. If it’s too high, things can melt or catch fire. Different people have different levels of comfort with temperature. But there are some some basic standards. Humans cannot exist safely in very cold temperatures or very hot temperatures without protection, and at certain extreme temperatures, there is virtually no protection available. Understanding this scale, and where on it we are more/less safe is very important.

Middle Ground? Is Rarely Ideal.

In a continuum or scale, you can have have too much or too little. It may seem natural to think that being somewhere in the middle is the ideal scenario. But it is not. It all depends on context. Like water and temperature, in some scenarios being right in the middle may not work. For example, in the range of temperature gradients on Earth, from -89C to +58C puts the “middle” at 15C, or 59F. That may be fine for humans, but billions of plants and animals may not be able to survive at that temperature. The same goes for water. There is no “perfect” amount of water. It depends upon the context.

Not knowing where you are on the continuum?

It may seem obvious… if you feel cold, put on a jacket, but sometimes we may not realize how much farther along on the scale we really are. For example, if you are out on a windy day, and the temperature is somewhat low but not dangerously low, you might think you have nothing to worry about. But then your feet or hair gets wet. In a situation like this you could be in more danger than you imagine. You could get hypothermia, and have your body temperature drop more rapidly. You could be in much greater danger than you realize.

Another example of this is the “Boiling Frog” story:

The boiling frog is a fable describing a frog being slowly boiled alive. The premise is that if a frog is put suddenly into boiling water, it will jump out, but if the frog is put in tepid water which is then brought to a boil slowly, it will not perceive the danger and will be cooked to death. The story is often used as a metaphor for the inability or unwillingness of people to react to or be aware of sinister threats that arise gradually rather than suddenly.

The boiling frog story demonstrates that temperature changes, if done gradually over time, may not be noticeable, and could lead to danger.

Imagine instead of temperature, we are talking about very subtle abuses a person is subjected to, that initially seems trivial, but over time manifest into more serious problems. This is how abusive and destructive relationships come about. It’s often a series of small steps that cause those in the, “boiling pot” to not realize the temperature is rising to dangerous levels.

This is why it’s important to not only understand the scale, but ways in which a small change on one side of the scale can lead to something much worse. And catch these situations early to avoid greater problems.

The solution to the “boiling frog” problem is to be “aware” of what temperature you’re in, and know what temperatures are safe and comfortable for you. And routinely measure the temperature of your environment.

Being aware of the parameters in which you are comfortable, and measuring those parameters, is the primary step to taking care of yourself. And understanding the dynamics of how your environment can change — sometimes without you noticing.

Empathy, like temperature is part of your environment that has a direct impact on your health and comfort.

The degree to which you are surrounded by people who care about you, whom you can trust, determines how safe and secure you will be. Like temperature, if you’re in an environment with extreme levels, it can be detrimental to your health.

Temperature is an abstraction, that we can measure. So is Empathy.

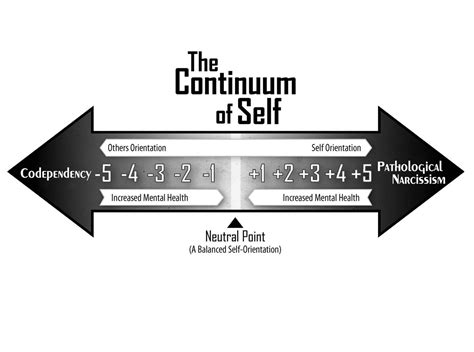

Empathy, compassion, concern, and feelings for others, like temperature, is not a yes/no thing. It operates on a continuum. Whether we care about someone else, and the degree to which we care, varies quite a lot based on a wide variety of factors: How well do we know this other person? Are they a stranger? Friends? Family? Do we have a history with them? Have they helped us before? Are they trustworthy? Etc.

Obviously a person is bound to have more empathy and concern for a family member or a loved one over a stranger. That makes perfect sense.

But when all things are equal, given any specific scenario, different people still have different levels of care and concern for others. Why is this?

Different people have different innate levels of Empathy

For better or for worse, this is the way things are. Some people are more caring and compassionate than others. Some people will help out a person in need on the street, and others will step over the same person.

NOTE: This is not a judgement on which type of person is morally superior. This is just a fact of life. We’re not here to make any wide-sweeping judgement of what types of people are better/worse.

It is up to you to decide what works for you. But the first step is recognizing: people are different. And sometimes some of these differences are “baked in” to our personalities and not easily or quickly changed.

Empathy is different from Understanding

Some people believe that empathy is the same thing as understanding. As long as you recognize the situation other people may be in, that’s considered “empathetic” by some. But empathy goes much deeper than that. While it is possible to empathize with someone and disagree with their situation or life choices, that’s not necessarily empathetic behavior. When you “put yourself in someone else’s shoes” you are thinking and acting as if their feelings and biases are your own — in that case, true empathetic behavior often involves not merely acknowledging other people, but validating their feelings. In such a case, empathetic people tend to agree with those with whom they empathize. And in cases where they don’t, it shouldn’t be for personal reasons – it should be for the greater good.

You can have empathy for others, but not agree with them: For example, you can have empathy for a pedophile and recognize that they have feelings and needs and genuinely care about children, despite their sexual interest in them. However, you disagree with their perspective and life choice, not because it conflicts with your own biases, but because you can empathize with another party, children, who can become victimized.

So in cases where someone empathizes with someone and disagrees, the nature of whether true empathy is involved, depends upon whether their disagreement is based on their own self-interests, or the interests of others (true empathy).

Here’s another example: Let’s say you are not in favor of healthcare reform because you are under the belief it increases healthcare costs for you, and you’re against that. You claim you “empathize” with those who don’t have access to affordable healthcare, but you still are not in favor of policy which would give them improved access if it hinders your personal costs. That is not empathetic behavior. That is merely acknowledging and understanding other people have different situations. If you really had true empathy, if you were in their shoes, you would be in favor of reform.

In this manner, empathy is a great equalizer. It lets you elevate another person’s perspective to match or even overshadow your own. While this may not seem advantageous to your personal interests, if you think of an entire society doing this, it does. Because other people too, will be putting your interests on a pedestal as high (or higher) than their own. And everybody benefits.

Is Empathy hereditary or environmental?

One of the things scientists in a great many fields of study debate about, is the degree to which high level human behavior is something people are born with, or learned through life experience?

In all likelihood it is a combination of both: genetics and environmental factors.

We know that there are many chemicals in the human body — the most obvious of which are hormones, that can make people more aggressive, paranoid and violent, or peaceful, altruistic and loving.

These chemicals naturally occur in the body at different stages or life, in

different scenarios, in different strengths. Women have an abundance of Oxytocin in their system, which lends itself towards the behavioral characteristics associated with procreation and protection of their offspring. In contrast the hormone Testosterone, more present in males, accounts for physical qualities that are necessary for defense, and can precipitate aggression. The levels of these and many more chemical compositions in the body affect our psychological outlook at any given moment. And ongoing patterns of behavior, be it altruistic, or aggressive, can foster the development of certain characteristics that in time, become associated with archetypes that people identify with.

In other words, humans are born a certain way, and develop a certain way. We are always changing, but to some degree, there is an “essence” of who we are, an identity that eventually emerges. This is often expressed as our “personality” or “temperament.”

These “archetypes” cover a lot of social characteristics: friendly, quiet, outgoing, introverted, emotional, logical, athletic, trustworthy, vain, funny, insecure, generous, etc. There are a million ways people can be described by themselves and others.

And each and every day, we interact with different people and, whether consciously or unconsciously, we size them up; we measure their personality according to our own needs and personal experience. It’s not any different from the way we process food. We have some cuisines we like more than others. We have some people we like more than others. It’s human nature. It’s un-avoidable.

Why Is Empathy So Important?

With so many human characteristics, what’s the big deal about Empathy?

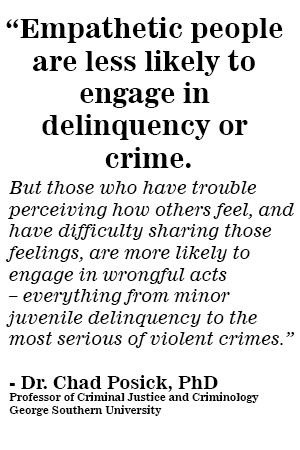

It turns out, empathy is one of the “source-elements” of social cohesion.

Where you find more empathetic people, you find healthier communities. You find lower crime. You find longer life expectancy. You find happier people.

The opposite is also true. Where you find people with limited empathy, you find more criminal behavior, more violence and suffering, lower education, more depression, and more atrocities and destructive things going on.

In A Community Setting, Having too little Empathy is much worse having too much

The value of empathy in most cases is circumstantial. In a time of war or survival, or competition, a single-minded sense of purpose, unclouded by the needs of others, may arguably be a beneficial perspective. But humans are social creatures, especially in our modern era, and as such, empathy plays a significant role in securing long term security and comfort.

At both ends of the Empathy spectrum, people suffer. Having too much empathy can result in a person feeling too much of the pain of others and unnecessarily suffering themselves, as well as being taken advantage of.

At both ends of the Empathy spectrum, people suffer. Having too much empathy can result in a person feeling too much of the pain of others and unnecessarily suffering themselves, as well as being taken advantage of.

But having a notable lack of empathy (known as EDD, Empathy Deficit Disorder) has much graver consequences. Sadists, Psychopaths, Murderers, Serial Killers and other criminals all exhibit significant lack of Empathy. It’s their cavalier attitude about the rights and feelings of others that pave the way for atrocious criminal and immoral acts.

In this manner, Empathy is somewhat like water. Too much of it, in specific forms can be destructive, but very little of it can be even more destructive to a wider variety of life. Water can support life, but very little life can exist without water. Empathy works like this as well. In a communal social environment, lack of empathy is highly destructive. A reasonable amount of empathy makes a community healthy and productive.

How can I use Empathy to make my life and my community better?

Now we come to the second and most important aspect of The Golden Path.

We’ve established that Empathy is a useful force personally and socially. But what does this mean for every day living? Can our understanding of how Empathy plays a role in relationships and our culture help us?

Absolutely it can!

We will address this in the next step:

How To Identify, Measure, And Use Empathy To Make The World Better