In the wake of the Covid pandemic, it’s become obvious there’s great division, especially in American society, between people who have embraced the collective wisdom of experts in the medical field, and those who cling to conspiracy theories and arguments that this worldwide pandemic is a hoax, overblown, or a vehicle for private interests to “take away people’s freedoms.”

There are many ways people are trying to deal with this conflict. There are many people who are frustrated over what they see as an incredible lack of empathy exhibited by so-called “anti-vaxxers” and “anti-maskers” who refuse to cooperate with guidelines designed to control a public health crisis.

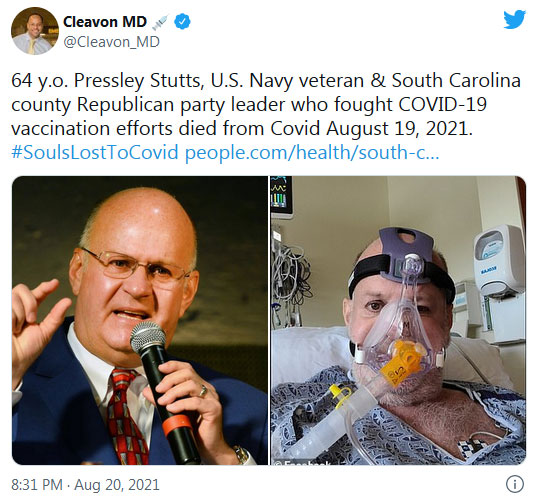

As time and natural selection confidently marches on, there’s been an ever-increasing pattern emerging: Those who dismiss the pandemic and its treatment are consistently falling prey to the repercussions. People who refuse approved treatments in favor of back-alley use of veterinary supplies, and other treatments not approved, are finding their beliefs aren’t keeping them safer, and freedom doesn’t seem to matter when a person is slowly suffocating due to oxygen deprivation. Yet many of these, people, even as they suffer at their own hands, are intent to continue to spread ignorance and misinformation.

This cognitive dissonance would be more excusable if these peoples’ irresponsibility only affected themselves, but it hurts everybody around them. It’s pushing the world’s healthcare system to the edge of its abilities, and healthcare workers to the edge of their sanity.

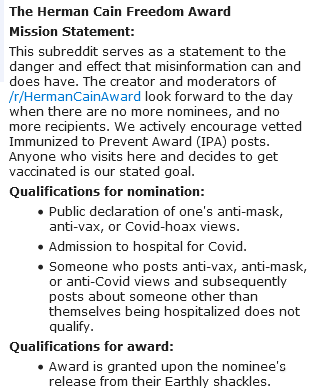

One isolated social media community found a way to reconcile with the grief by turning these anti-vaxxer’s stories into cautionary tales, provoking controversy as well as providing a place for people to vent and attempt to reconcile their frustrations with their fellow humans. One such place is Reddit’s “Herman Cain ‘Freedom’ Award” subreddit, named after a prominent Republican political leader, who notoriously mocked Covid and precautionary measures and passed away from the disease. Subsequent outspoked anti-vax pundits and everyday people spreading unscientific memes on social media have been made examples of, even as they struggled to live and continued to refuse to admit they were wrong. Many are leaving behind families, children, even the unborn, all the while their remaining relatives establish online money pandering efforts to cover the huge healthcare costs racked up by the, “overblown flu hoax.”

It turns out, many burned out healthcare workers in the industry have congregated in this social media space as a way to help deal with all the unnecessary death and suffering they’re subject to on a daily basis. The added context, while tragic, helps many understand and explain the nature of suffering a little better.

Mainstream media has discovered places like this and sought to vilify those calling attention to the demise of anti-vaxxers as some kind of psychopathic circle jerk. But the reality is, it’s the opposite. Sometimes, empathetic people need an outlet to vent and release their frustrations in dealing with those who have so little empathy.

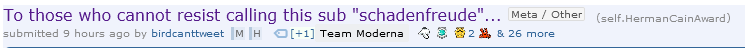

Here’s a response from user “birdcantweet” on Reddit when confronted over whether or not singling out anti-vaxxers that end up dying is considered “Schadenfreude”. This short essay is a great example of the intricacies and complexities of empathy (and lack thereof).

“..please stop. That is not the word. Schadenfreude is joy at another’s misfortune, and there is nothing unfortunate or undeserved about what is happening to our honorees.

The ancient Greeks called it tisis. The Romans called it Nemesis and personified her as a winged goddess. Popular culture calls it karma. All have the same basic meaning: retribution. Not retribution from human hands for the violation of human laws; retribution from the outraged universe itself, a bitchslap from Mother Nature to those who tweaked her nose one too many times.

At this point, the antivaxxers have self selected into a particular tribe: generally white, lower-to-middle class, ‘evangelical’ or charismatic Christian, politically conservative, and often explicitly pro-Trump. They claim the virtues of courage, wisdom, faith, and prudence; they have instead the vices of apathy, ignorance, recklessness, and a lack of empathy. And this last is the fatal flaw, because it renders them unable to see as human anyone who is not just like them. And their social media posts, both in their original content and the memes they share, have no purpose except to cement their standing in the tribe. The memes are, to put it gently, repetitive. But to a tribal mindset they are essential; posting the same badly-captioned picture of Dr. Fauci does as much to prove membership as staying exactly in step in the fireside dance.

The maxims of the tribe are simple:

- We will not get COVID.

- We don’t care if you get COVID.

- There is nothing you can do to make us care.

And on they go, happily enjoying their freedom while the rest of us ‘live in fear.’ And those of us not of their tribe — you know, those of us who have empathy, who have understanding, who can find solidarity even with the members of the human race who are not our color or gender or religion because we’re all f%^$^g human — grind our teeth. Because while they swagger along like the bully’s little sidekick, COVID continues to ruin lives, and they don’t care.

Then they hear the brush of feathers at the window.

In some cases, human suffering produces empathy. We celebrate that.

In some cases, fear of suffering — appropriate, reasonable fear — shakes people out of their complacency and makes them take steps to protect themselves. We celebrate that too.

But in other cases, ignorance and apathy tip the scales too far, the laws of nature snap back, and the consequences come due. We do not celebrate that. But we do admit to finding it satisfying, because it justifies our own course of action. We chose fear, yes — but it was a wise fear that led to health and life. We did not choose faith — at least, not faith without works. We celebrated medical science, and those of us of a religious bent (myself included) thanked God for giving humans the minds and tools to produce a vaccine just when we needed it most. And we did care — and continue to care — about those who prove their tribal identity by slandering everyone else. We care about the broken families and burnt-out caregivers left in their wake. We don’t celebrate their passing, though we don’t mourn them. And we don’t call them unfortunate. They have received what they were seeking all along.

Antivaxxers act as they do because they feel proof against the consequences. They are wrong. Until ignorance becomes more painful than knowledge, their ignorance will continue. That is where we come in.“

What is it that makes anti-vaxxers so immune to evidence, logic and reason? Is it the information bubble they have been subjected to? Mental illness? Paranoia? Ideological indoctrination?

There are many potential correlations between this antisocial mindset and various external sources, from religious and political groups to news and media sources, to cultural peer pressure.

But at the end of the day, the primary function that allows a person to ignore the suffering of others is lack of empathy. Proving once again, especially in cases like this, that empathy can be a great force for healing and comfort, and lack thereof, a tremendous force for destruction. Humans continue to wrestle with how best to handle the toxic among us. We’ll continue to investigate and report on this.